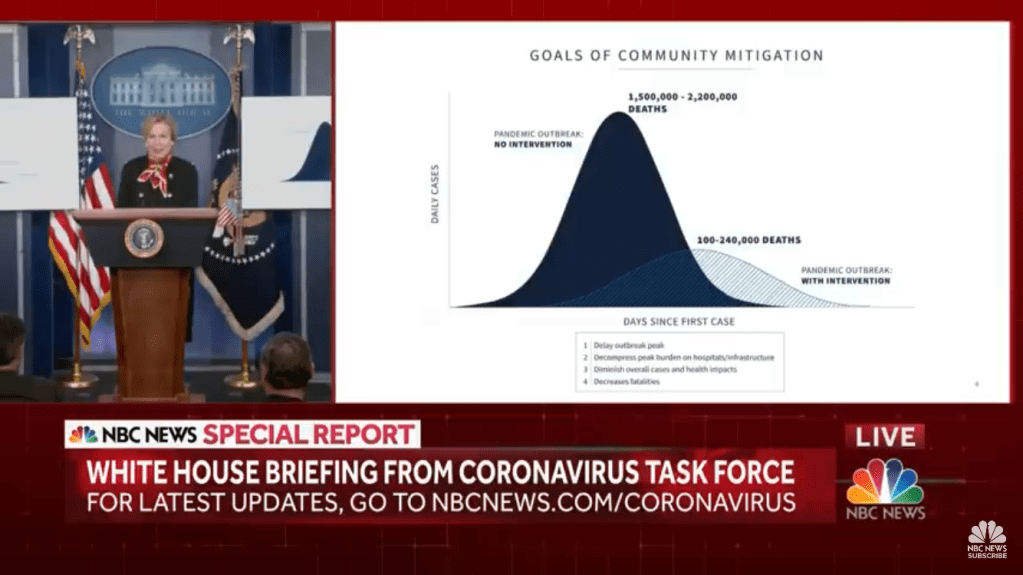

100,000-240,000 projected by the Task Force.

Full presser here. We get the introduction of “30 Days to Slow the Spread,” after the first “15 Days to Slow the Spread” have concluded.

I want to talk about the good, the bad, and the ugly of this presser. But not in that order.

The bad news

First, I want to discuss the grim news. The projections of high-five to low-six figure mortality are inevitable at this point. Even if we do a fantastic job at what we are being called upon to do, so many folks had contracted the virus earlier this month—many very early, before sportsball shut down and all the rest—and they have to go through the process of hospitalization and ICU before they succumb. They need our medical system to come through for them now.

It is going to be a rough fortnight ahead. My area is going to be hit pretty badly—maybe not as bad as New York, but still notably taxed. Michigan lost 75 today, which appears to be above the maximum predicted by the latest IHME model for today.

The hopeful news

Do you realize how much can be done in 30 days? Or 45 days?

Let me illustrate.

According to this tracker we lost 748 souls today. In this paper, the author estimated that one death today represents about 800 current cases. That depends on variables like spread rate and fatality rate, which nobody really knows with any certainty. But for my purposes I am going to estimate that there are 1,000 active cases of Coronavirus in this country right now, for every person that died today.

That’s 748,000 infected people, or about 1 in 445 Americans. Or 2,246 people per million.

So we are now going to do severe mitigation for 30 days. We are being asked to shelter in our homes as much as possible. If we go out, it is to only exercise and get food and run essential errands, and do essential work that cannot be done at home.

Let us assume that, prior to March 11, when the NBA shut down and Trump gave his Oval Office address, each person with the bug gave it to 3 new people over a 5 day period, and that this happened every 5 days. The person who had it originally eventually resolved it or succumbed to it.

Since March 11, people started changing their behavior, so that they would share the bug with a lot fewer people. But that change took some time, and not everyone was on board.

But today, we have 748,000 people carrying the active bug. They are now called upon to not share the bug, if they have it. If they don’t have it, they are called upon to avoid contracting it to the greatest extent possible. Of course, most Americans don’t know which group they are in.

Let’s assume we perform this mitigation to the extent that only half of the 748,000 pass the bug to one person each, and the other half do not. (This happens on net: some people may share with 2 people, a few with 3; while a lot more will not share it at all.) After 5 days, on April 5, there are only half the bugs left: 374,000.

The new 374,000 share it with half over the following 5 days. On April 10, you have 187,000.

Through the next 20 days, you get to cut that number in half 4 more times. On April 30, you will have 11,688 people in the entire country with the bug. That’s 1 in 28,491 people in America. It’s 35 per million.

Here are some other possibilities for remaining bug count, with different levels of mitigation. Assume every 10 people passes it to the following numbers of people every 5 days:

- 11 people (growth): 1,325,127 (4,015/million)

- 10 people (maintenance): 748,000 (2,246/million)

- 9 people: 397,518 (1,194/million)

- 8 people; 196,084 (589/million)

- 7 people: 88,001 (264/million)

- 6 people: 34,899 (105/million)

- 5 people: 11,688 (35/million)

- 4 people: 3,065 (9/million)

Although the actual numbers may be significantly different than what I assumed, you can see that you can knock the bug count down to a level for which you can address individual cases without interfering with everyone’s way of life.

With the new Abbott tests, I am hopeful we can identify any positive cases quickly at that point, and warn the local communities to have their people tested to catch any others before it gets out of control again.

Of course, the probability of the virus being in your area will vary from place to place. I live in Wayne County, Michigan, an emerging hotspot, so I have to be more careful than people upstate. People in the New York City and New Orleans areas, likewise.

The guidelines

My favorite detailed description of exactly what to do to mitigate.

With regard to mask usage, there’s a public debate about how effective they are for laypeople. The President commented on it during his presser, as did Fauci and Birx; and the Surgeon General has his view.

I would really like some clarification on exactly how effective masks are for laypeople at mitigating this virus. In my view the need is going to depend on individual preference and habit.

According to the Cornell doctor in the video I linked above, the virus spreads most readily via droplets. A person touches their face, then touches a surface with their hand. The next person touches the surface with the hand and then touches their face. The goal is to cut off that transmission path at one or more points.

It seems to be that a mask—whether non-medical, surgical, or N95—has questionable value as a reliable physical barrier if you do not have Covid already. It can be defeated if you unconsciously touch your face or adjust the mask. Possibly you can transfer a droplet onto the surface of your DIY mask and then end up breathing the virus in through the fabric over an extended time (if not an N95 mask).

But if you want to train yourself not to touch your face all the time, the mask can help you do that. And if you do need to adjust it, you can wash your hands before you do it, so you can do it safely. In that manner, the mask works as a psychological aid.

If you have Covid and you haven’t developed symptoms yet, the mask will block droplet transmission from your mouth. Once you get symptoms, of course, into quarantine you go.

Another transmission route you don’t hear much about is fecal-to-oral. So if you gotta use a public restroom, definitely scrub up before you leave that room.

The ugly

Jim Acosta asked stupid Acosta-style questions. Unlike yesterday—which was a complete waste of time—his main question this time is worth discussing here. He asked Trump and the task force if things would have been substantially different had they started mitigation back in February or earlier.

Of course, he asked it to get a cheap CNN sound byte, because CNN gotta CNN. But I found the task force response quite interesting.

The blunt truth is that days do make a huge difference when dealing with this type of threat.

Trump, of course, pointed out that the US bought a lot of time by cutting off Chinese immigration in late January. But both Drs Fauci and Birx pointed out that they really didn’t know how much virus was in circulation several weeks ago. If there wasn’t a lot, then mitigation would not have been warranted.

I think it is readily apparent that the virus was with us in places like New York during mid-February—and New Orleans during Mardi Gras weekend—because people died of it several weeks later in mid-March. The trouble is that we really do not know how much.

Nobody really agrees on the some of the main parameters that determine how destructive Covid-19 is. For instance, you have a moderate spread rate and a moderate fatality rate, or you could have a really high spread rate but a much smaller fatality rate.

Either combination can result in the mortality we are seeing everywhere without intervention—but the methods for proper intervention are different each combination. The percentage of asymptomatic cases is also very important.

This onerous mitigation procedure we are undergoing may not be warranted, but we really don’t that right now, because we don’t know enough about this disease. Almost nobody trusts the Chinese data in its entirety.

Anyway, we will know so much more about this disease in one months’ time. It will feel like a year. I hope the spring weather gives us an assist on the noble mission we all are on this month.

Good luck and God bless all of you—and God bless the U.S.A.

One comment